The Complete History of Damn Yankees

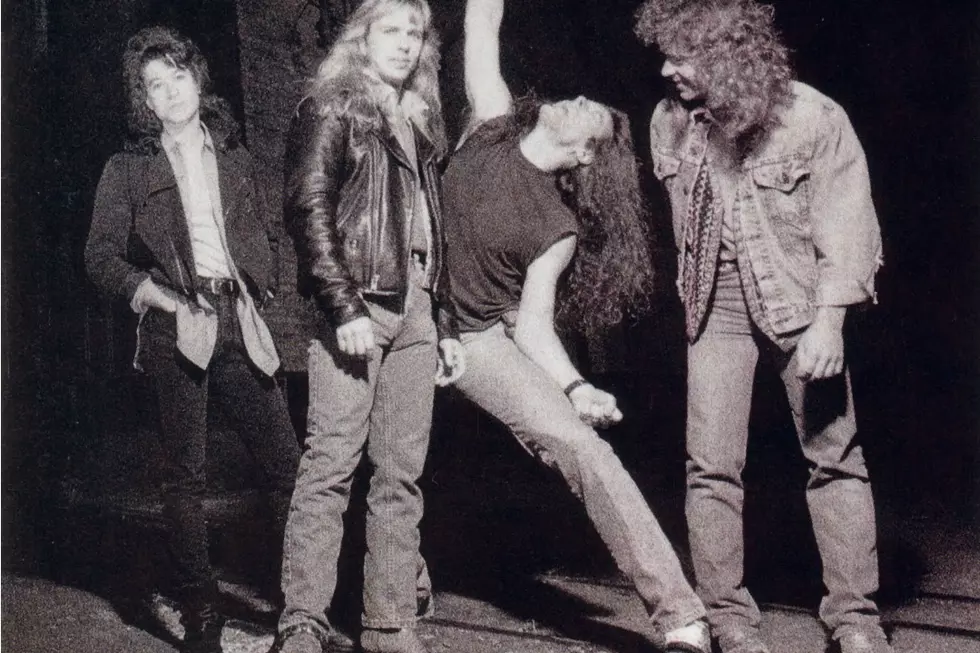

The late '80s found Ted Nugent in the midst of a decade-long career lull that reached its nadir with his 1988 LP, If You Can't Lick 'Em ... Lick 'Em, petering out at a lowly No. 112 on the charts. Former Styx guitarist Tommy Shaw, meanwhile, had gotten off to a bumpy start with his solo career — his third album, 1987's Ambition, failed to chart — and Night Ranger bassist Jack Blades was at loose ends following his band's dissolution at the conclusion of the tour for their 1988 Man in Motion release.

Most rock fans were aware of the career conundrums facing the trio, but only one man had the foresight to see how well they could work together: legendary A&R guru John Kalodner, who shepherded Blades, Nugent, and Shaw into the principal parts that — along with drummer Michael Cartellone, who'd served a tour of duty in Shaw's solo band — eventually made up the supergroup Damn Yankees.

Ultimate Classic Rock spoke with each member of the band about their double-platinum 1990 debut album – as well as Kalodner and producer Ron Nevison – to take a comprehensive look back at how these unlikely-seeming bandmates came together in pursuit of rock & roll glory.

"I just had this idea – I think I had dinner with Jack Blades or maybe Tommy Shaw and for some reason, I got in this mindset," Kalodner tells UCR. "I knew Ted Nugent well and he wasn’t really doing anything. Night Ranger wasn’t really doing anything, and Tommy Shaw was kind of in and out with Styx. So I came up with this crazy idea to have the three of them have a supergroup."

Of course, it's one thing to have an idea, but only a few ever have enough music business mojo to make the right people listen. Fortunately, Kalodner was riding an extreme hot streak at the time after being involved in hit records by Aerosmith and Whitesnake, and his post as the head of A&R for Geffen put him in a unique position to get the managers for Blades, Nugent, and Shaw on the phone. As Kalodner remembers it, he started with Shaw's rep at the time, Bud Prager.

"He said, 'Well, that sounds really crazy, but let me ask Tommy,'" recalls Kalodner. "I knew Doug Banker, Ted Nugent’s manager, and I called him. I asked Jack Blades. They said, 'Well, that really sounds nuts.' Ted Nugent particularly thought it sounded like a stupid idea. But I convinced them to all get together and meet at Bud Prager’s office in New York. He had a small rehearsal room there, and they played together for a few minutes and decided that they would give it a try. That was in the late spring of 1989. So it was kind of a fantasy that I had to put these people together. None of them even knew it or had even thought about it."

All of which may be true, but according to Nugent, Shaw had Nugent's personal seal of approval. "I always admired his soulfulness," he insists. "I was the only one who really stood up in defiance of the claim that Tommy Shaw was this cute little blonde towheaded cherub playing pretty Styx music. I knew that he was a huge black man from Montgomery, Alabama, raised on the same blues of James Brown, Wilson Pickett, Sam & Dave and Motown that I was."

Once he and Shaw got together, Nugent says the musical gratification was immediate. "God, it wasn’t minutes, it was seconds," he recalls. "Within seconds, we just picked up a couple of acoustic guitars and we started playing these grunting, grinding, soulful grooves and patterns, kind of like honky tonk meets boogie-woogie bastardized...and 'Come Again' happened."

Watch the Video for 'Come Again'

"Interestingly enough, I came up with the guitar part and Ted wrote the words," Shaw says of "Come Again," which later ended up on the Damn Yankees album. "He was courting the new woman in his life, Shemane, and it was funny, because he showed up and his hair was all poofed out and he had these leather pants on and boots and he was all dressed up. It was like, 'Man, Ted’s like a sharp dressed man!' Well, it’s because he was trying to make a good impression. After a while, you know, it’s flip flops and socks and hunting clothes. That’s the Ted that we know and love."

As much fun as that initial session may have been, Kalodner felt like there was still something missing. "A guy named Norm Dahlor was playing bass at the time," Shaw continues. "Ted and I wrote 'Come Again' and there might have been something else, but that happened pretty quickly. But Kalodner was still thinking that maybe there was a missing link. Jack came to John and said, 'I’m looking for something to do – Night Ranger’s breaking up,' and he said, 'Well, I want you to go to New York and work with these guys.' That’s when Jack showed up and then within about a half hour, we’d written 'High Enough.' So all of a sudden it went from being really good to 'Holy shit!'"

As Blades tells it, he got the phone call from Kalodner less than a week after Night Ranger played the final show of the Man in Motion tour. "He said 'Look, I have Ted Nugent and Tommy Shaw working on these songs in New York City. Something's not quite there, it's not quite right and I think maybe you'd be the catalyst for it,'" he recalls. "He sent me a plane ticket and flew me to New York, and I just ended up on the porch of Tommy Shaw's brownstone on the Upper West Side in like 1989. It was like, 'Wow,' and that first weekend we all got together and wrote about half the record, that first weekend. We just went in and started tearing into it. Tommy and I, sort of, like, found ourselves as kindred spirits. I'm sure we were like separated at birth, you know? It was just an instant rapport, an instant everything. It was a little bit different with Ted, but with Tommy it was like that. Boom. It was done. From that point on, Damn Yankees were rocking."

Although Blades had gone his separate ways from the other members of Night Ranger, who'd later record an album without him in the mid-'90s, there wasn't necessarily any animosity. In fact, if Cartellone hadn't worked out, Blades says Night Ranger drummer Kelly Keagy was waiting to step into the breach — but according to Nugent, he knew immediately that Cartellone was the right man for the job.

"The enthusiasm for what we were creating erupted instantaneously," Nugent tells UCR. "Cartellone impressed me right away as a grinder too, you know? He right away hit the backbeat and he was on the top end of that backbeat, which turned me on."

"When Tommy called me that day and asked me to come by, I hung up the phone and thought, 'This is going to be really cool, and it’s never going to work," laughs Cartellone. "Because on paper, Tommy and Ted seem to be at polar opposites stylistically. It wasn’t until getting in that room did I see how much R&B common threads they actually have. Jack had the background of not only the R&B, but Jack also had the background of the more hard rock that leaned towards Ted and then the more melodic rock that leaned more towards Tommy. It really just became the perfect balance."

Ultimately, while Nugent's aggressive lead guitar work would give Damn Yankees' songs more of a sting in the tail than Blades or Shaw had enjoyed with their previous bands, quite a bit of the band's appeal rested on their vocal and songwriting blend — and as Blades points out, although these things are never a given, their shared background as members of melodic rock bands with multiple vocalists definitely worked in their favor.

"It was very easy for both Tommy and me," Blades nods. "Tommy with Dennis DeYoung from Styx and he was used to just jumping right in on things, and myself with Kelly Keagy. It was sort of like a unique situation. We know the ins and outs of that kind of stuff. ... Tommy's voice and my voice work well with anybody. Together it was very easy for us, because Tommy's got that wonderful super-high — I mean, I can't sing that super-high, pure. I'm in that middle range, but I have this real high falsetto that I can go really strongly above his super-high voice. Like on 'Come Again,' you know what I mean? We started singing together, and we were like, 'Well, this is easy!' It was one of those deals."

While Blades and Shaw were immediately on the same wavelength, everyone involved knew it would take a little extra effort to make sure Nugent's over-the-top guitar antics fit in the framework of the songs and the band's overall sound. As Kalodner puts it, "Ted Nugent knows that I was one of his biggest fans and I spoke always in that way. During the formation and early rehearsals of the band, I told him he was going to have to like calm his ass down. Everybody knows he’s a great guitar player, but it’s not that kind of band, so he was really going to have to think about [not] playing over, jerking off the guitar all over the songs that they were going to do, or the band would be a failure."

"You know, everybody goes, 'I can’t believe Ted Nugent could be in a band, he’s such a domineering prick!' Being a domineering prick is a lot of fun, but it’s not a full-time job!" laughs Nugent. "I improvise and adapt and overcome. I’m only a domineering prick when I have to be." In fact, he recalls coming up with the band name during a completely off-the-cuff moment: "They said, 'Well, what would we call the band?' Immediately, I didn’t think about it, I went, 'Well, we’re a bunch of damn Yankees, let’s call it that!'"

Listen to Damn Yankees Perform 'Mystified'

His lineup in place, Kalodner got the band up on stage at New York's China Club on May 4, 1989 for an off-the-radar performance so he could see how a crowd would react to the evolving Damn Yankees blend. "We played 'Come Again' and 'Mystified' and if memory serves, we probably played 'Cat Scratch Fever.' The audience certainly wasn’t expecting to see those people walk on stage," laughs Cartellone. "Kalodner was standing right in the middle of the club and was looking around at peoples’ reactions with a big smile on his face thinking, 'Oh yeah, there’s something there.' It was a really, really cool night."

According to Blades, Nugent phoned Kalodner after the show to complain about the bassist's stage presence — "Jack's moving around too much, I don't know about this, I don't know about that" — and their resulting showdown ended up cementing a brotherly bond that continues to this day.

"I said, 'From this point on, Ted. Straight up, if you want to say something to me, you tell it to me. If I have something to tell you, I'll tell you. Let's get that straight right now,' and Ted said, 'Yep! That's fine with me. That's good,'" he recalls. "From that point on, Ted and I have been the best of best friends. I think a lot of people have always just been 'yes men' to Ted. ... The fact that we can speak frank with each other was very refreshing for Ted. So that really worked out. I think that helped out in the very beginning to enable Damn Yankees, we checked our egos at the door. From that point on, we were just a bunch of buds, just laughing and joking and coming up with ideas."

"Ted was a band guy in the Amboy Dukes prior to having his solo career success. So Ted knew how to be a band guy," notes Cartellone. "Ted is certainly a large personality...I mean, he fills a room. But I will say, it was really interesting to see the way that people checked egos at the door."

The ideas they came up with included "High Enough," the album's big power ballad, which Kalodner knew was a hit as soon as he heard it. "I said to Tommy and Jack that they had to write two commercial hits and I’m sure that they could do it," he recalls. Between "High Enough" and the record's leadoff single, "Coming of Age," Kalodner was confident he had enough to get the band rolling at radio. "In the era that we made these commercial radio records, the rule was that you only really had to have four commercial songs, five at best," he points out. "The rest could be the shit that the band wanted to write."

Of course, hearing Ted Nugent deliver a wailing solo over a power ballad wasn't what many people expected to hear in 1990, and Blades admits that he and Shaw were well aware of how the song might go over the first time they played it for him. Recalling that it came together during a half-hour writing session spurred after Shaw heard him singing the vocal melody while doing his laundry in the basement of Shaw's brownstone, Blades still laughs when he remembers Nugent's initial reaction.

"We thought he'd be like 'What the fuck?' We thought he would totally reject us, the song, the whole thing. Finally we were like, the hell with it. Let's just go play it for him," Blades tells UCR. "Ted's just sitting there, chewing on a fricking toothpick or whatever he does. Just sitting there, listening to the song, nodding his head and shit like that. We're like, 'Oh, he fucking hates it. He fucking hates it.' He's gonna get the gun out and shoot us right there. Boom. That's gonna be the end of Damn Yankees. Tommy Shaw and two others, killed by Ted Nugent."

The rest was rock crossover history. "When we finished the song, he sat back in his chair and goes 'Hmmmmmmm,'" continues Blades. "He kinda shook his head and said, 'You know what that song needs?' and we're like, 'Okay, here it comes. It needs to be gutted and thrown on the gut pile or something. What, Ted?' and he says, 'It needs this' and he has his guitar and goes [imitates guitar noises] and Tommy and I look at each other and say, 'Yep, that's exactly what it needs!'"

"I think somebody actually uttered, 'This doesn’t sound like a song with Ted Nugent in the band,'" Nugent laughs. "I said, 'Fuck you! I’m a gentle soul! I’ve never made love to you, so you’ll never know, but I work my way up. I’m good at foreplay. Shut the fuck up, let’s play this song!'"

Such is Nugent's love for the song that he says he defended it against Zakk Wylde when Wylde, guesting on a TV show, used "High Enough" as his justification for suggesting that Nugent had gone soft. "He was doing his best to be me with his armbands and his Hells Angels regalia, which I think his wife dresses him up in. It’s hysterical. What are you doing?" recalls an incredulous Nugent. "'I can’t believe Nugent went pussy on me.' Believe it! If you had a shower, you might be able to understand it better, fuckface! And I love Zakk Wylde, by the way. I’ll never forget, he was condemning me for being in the Damn Yankees and playing 'High Enough.' That’s a killer fucking song!"

Watch the Video for 'High Enough'

Unfortunately, it wasn't enough to get Damn Yankees in the door at Geffen Records. Even though he'd brought the band together and bankrolled their demo sessions, Kalodner hit a wall when it came to getting the Damn Yankees greenlit with Geffen president Ed Rosenblatt — and it ultimately cost him his involvement with the band.

Recalling that Rosenblatt told him "The promotions team thinks that it will be a success, but we don’t need another corporate rock band so I can’t let you sign this band," Kalodner admits, "I was really stunned. Really, no one’s ever asked me about this story until now. But that’s the real story. You know, that’s something that at the time, I wouldn’t go to David Geffen, because Ed Rosenblatt ran the record company. We really hadn’t had any failures in communication, but he just put his foot down and said, 'I can’t let you sign the band.'"

"Geffen passed on it. So I took the same demos into a friend of mine who ran Warner Bros. Records, Michael Ostin," continues Blades. "I played the first song, 'Coming of Age,' and then 'High Enough' was second, and he got past the chorus and stopped it. He said, 'Have your attorney call us in the morning. It's done.' He heard it and that was it. He had his staff in there." It all happened so quickly that Blades — who was there with his manager Bruce Bird's brother, Gary — didn't know it was over. "I'm still in there pitching, 'Man! We can be great! We got Nugent!'" he adds, laughing. "Gary pulls me out of the room and says, 'Shut the fuck up, will you? Don't say another word!'"

Contract in hand, Ostin reached out to Nevison, who says now that he "flipped out" when he heard the demos — particularly "High Enough" — and headed out to Blades' Northern California home for rehearsals in October of 1989. "That was when the earthquake happened on Oct. 17, 1989," recalls Nevison. "We were in the basement and we were all baseball fans, and Ted could care less about that. We wanted to finish up before the World Series game started at 5, so we had been working all day. I felt a note that was way lower than anything on the bass and I felt this rumble and I looked down and through the door, I saw the water in Jack’s swimming pool lapping, and I went, 'Oh, shit!' ... I ran out the door and Jack said, 'No, you’re not supposed to run outside during an earthquake,' and I said, 'Get out of my way,' and I ran outside!"

Earthquake aside, Cartellone says those rehearsals were a crucial component of the smooth sessions for the Damn Yankees LP. "Oct. 23, 1989 is when we began recording the record and it was a Monday. I think we had it wrapped by the middle of November," he recalls. "We had booked two weeks at A&M Studios to do the basic tracks and we used half of that time and we were out of there. So we really were very efficient once we got into the studio [...] The week before we went into the studio in L.A., we were still up at Jack’s place in Sonoma County, just doing some pre-production rehearsals. Ron Nevison suggested that we go into this little local 24-track demo studio not far from Jack’s house. We spent a day in the studio and we actually recorded the album live top-to-bottom. Consequently, getting that under our belt was really a brilliant suggestion from Ron, because then a week later when we were in the studio in L.A., we were very comfortable, like, 'Oh, okay, let’s run it again.'"

"It was not something I did all of the time, but I thought that because we were rehearsing in a basement at Jack’s house, no one could hear anything," Nevison explains. "I think maybe we stopped if somebody had made a huge mistake, but that was the whole idea of my idea, so people would know what we were going to do when we got to L.A."

According to Nevison, he was brought in because he was supposed to produce one of the albums Night Ranger recorded before their 1988 split and Blades still wanted to work with him, but Shaw believes Kalodner may have had something to do with it. "Ron is a very strong personality and all of us are used to having our own way in the studio and John didn’t want it to literally be a free-for-all. He wanted somebody who would be a good coach and not be pushed around by anybody in the band. We were all glad to have that, honestly," he admits. "There never really was any pushing and shoving, it was Ron giving great advice and being a team player and, 'This is how I’m going to bring this craziness together and make it make sense.'"

"That guy's been working on records since Physical Graffiti and Quadrophenia," adds Blades. "Ron Nevison has the kind of résumé most people would just dream of and die for."

"Ron Nevison’s production is spectacular," agrees Kalodner. "His recording of the Damn Yankees album was not spectacular, because he used a digital machine, which kind of gives it a little bit of an edgy sound. But his production, I would rate it a 100 out of a 100."

Nevison's résumé didn't keep him from locking horns with Nugent, however. Explaining that he believed his and Shaw's guitars needed to be way up front in the mix, Nugent remembers arguing over the mix so often that, at one point, Nevison started telling him to turn down before he'd even plugged in. "My amp wasn’t even on yet and he hit the talkback button from the control room and he goes, 'Ted, you’re going to have to turn down a little bit.' I hadn’t even played anything yet," he laughs. "I went, 'Hey Ron, if you really look closely, you’ll notice that was too loud before I fuckin’ got here!' I don’t know if Jack and Tommy and Michael remember that. But I love Ron. Ron’s a genius and he’s a killer guy. I’m glad he was part of the team."

"He was a tough guy," concurs Shaw. "Nevison, he doesn’t beat around the bush, so he kicked my ass a few times. I’m not sure if I wouldn’t have just gotten the stuff otherwise, but that’s just how he is. He’s a tough coach. But we got it and Ron and I are still friends, so it all worked out."

Watch the Video for 'Coming of Age'

As Nevison tells it, he actually wanted more of Nugent on the Damn Yankees record, which arrived in stores March 13, 1990. "He came up with riffs and he co-wrote some of the songs, but it wasn’t really his kind of music," Nevison explains. Saying he envisioned an album where he'd have two brilliant guitarists playing off each other, Nevison says he found himself "like a film director, having to do stuff without the other actor in the scene" when Nugent decided he wanted to record his contributions all at once.

"It wasn’t bad," Nevison hastens to point out. "Tommy’s great, and Ted came in and did his stuff. Ted wanted to come in and do everything at once. I think he made two trips. He came in once to do all of the rhythm guitars and then he came back to do all of the solos. But he wasn’t there for the album, basically."

But even coming in cold, Nevison admits that Nugent delivered the goods when that red light came on. "He didn’t even know what key the song was in. He had totally forgotten the tune. But being Ted Nugent, being the cocky son of a bitch he is, he just started playing and within 20 minutes, came up with a great solo," he recalls. "This guy just had so much confidence that he didn’t really have to rehearse – that’s not the way he does things. You know, that’s not a black mark on Ted, but it surprised the hell out of me."

"He didn’t even really have to learn the songs, he’s just got such a great ear," adds Shaw. "Like if you listen to the solo on 'High Enough,' the solo is in E, but he plays the solo in C-sharp minor. So he’s playing it in the [relative] minor of E and I didn’t even realize it. I was like, 'How is he playing that? Where is that coming from?' [...] In this major key, he plays a blues solo, and it’s stuff like that that just happened naturally because of who everybody is. That doesn’t always spell greatness, but in our case, it was the path of least resistance and it made things fun. There was always a little bit of the unexpected with Nugent."

"I’m a raw instinct primal scream guy. I don’t burden myself with wasteful thought processing," shrugs Nugent. "Something as instinctual and impulsive as music, you’re going to kill yourself and probably kill the spirit of the potential song if you contemplate what direction it might want to take."

His guitar ended up being a major part of the album, but Nugent only came away with one vocal number on Damn Yankees — the closing track, "Piledriver." "Well, when you’re surrounded by Indy drivers and you’re going to the store for milk and bread, let them drive," he laughs when asked about taking a vocal backseat to Shaw and Blades. "You know, those guys are such incredible vocalists, my goodness. I mean, let the big dogs run."

Listen to Damn Yankees Perform 'Piledriver'

For Kalodner, having the Damn Yankees record slip through his fingers remains "one of the biggest disappointments in my career," and it isn't difficult to see why — aside from the unique story behind the project, there's the fact that it spun off a pair of crossover radio hits and sold in the millions, as well as the fact that he was unable to offer his input when it came time to record the second album, 1992's Don't Tread, which he deems vastly inferior because "They wanted to just make an easy second record and collect the money from Warner Brothers."

Don't Tread sold respectably, but it ended up being the band's swan song. Damn Yankees would reconvene periodically in the studio during the balance of the decade, but multiple stabs at finishing a third album — some at the behest of Kalodner, who signed the group while at the helm of Sony's briefly revived Portrait imprint in the late '90s — amounted to little more than memories and a stack of songs that leaked out in dribs and drabs on the members' solo projects. Blades and Shaw recorded a duo album, Hallucination, in 1995, and two years later, they were back with the revived Night Ranger and Styx. Nugent, meanwhile, returned to solo action with 1995's Spirit of the Wild.

"I think we can all agree that the greatest philosopher of all time was Dirty Harry when he said, 'A good man has to know his limitations.' I think that the two records and the thousand concerts that we did, I think it was time for a break," suggests Nugent, recalling a particularly fruitless round of sessions with a producer who "came in with some kind of Boy George fetish or some ‘90s formula fetish instead of respecting the R&B camp we came from." Unable to get what they wanted out of the project, they simply let it go.

"I’m angry at myself that I didn’t fight harder to get the guy thrown out [so we could] stick to our musical beliefs. Because we recorded it and it was a joke," he insists. "It was a heartbreaker. Of course, I had other commitments and I had other things I had to do, so it’s not like we could spend a couple of months recording a record and then decide it sucked and go in and do it again. I had things I had to do and so did everybody else."

"His name is Luke Ebbin and Luke is best known for the Bon Jovi album with that song 'It’s My Life,'" recalls Cartellone. "He produced that. So yeah, Luke was in place to produce that record, and frankly it was probably not the best position to be put into, because it was so disjointed right out of the gate."

"There was a scene change. That was right around the time that Nirvana changed everything. It was time," adds Shaw. "Because there were starting to be these derivative bands and producers were coming up and creating bands that were in that same genre, and that always spells that the end is near. Somebody comes in and plays simple songs and all of a sudden clears the boards again, and it’s a reset. We were due for a reset."

"It just got interrupted by the way things were. That was kind of it for me. Because I had had thyroid cancer and then I came back and I was trying to work with them because I still believed in their talent," remembers Kalodner of the band's Portrait stint. "I just couldn’t get any help from anybody to back them."

"You basically had four people with four very separate careers," points out Cartellone, who joined Lynyrd Skynyrd in 1999. "There was another guitarist, a singer/songwriter named Damon Johnson, who got involved and co-wrote some stuff with Jack and did some recording as well. But the way that thing was recorded was very piecemeal. Because you had people flying in and out, going to their respective tour for their respective band, but then flying in and tracking for a couple of days and leaving again. At no time was that entire group of people ever in the same room. [Laughs] I think that understandably lent to the fact that maybe it just wasn’t meant to be."

Watch the Video for 'Don't Tread'

"That will never come out," agrees Blades. "It will always be the long lost record. Little pieces of that have dripped out on my solo record. Tommy had a song on Styx's Cyclorama record. Ted's done two or three of them. It's been hard to figure out, like, 'Oh yeah! That was one of our songs.' It's pretty wild. That record will never see the light of day, but the ones that came out are the best of it."

Even if that third album wasn't meant to be, the band members look back on their time together fondly. "Nobody had any pressure. Nobody put pressure on anybody to perform, everybody was just always champing at the bit," reflects Nugent. "The Damn Yankees represents the American dream, getting up early, putting your heart and soul into everything that you do, taking good care of yourself to get a good night’s sleep so you can do even more the next day. It was an absolute joy to be surrounded by that work ethic, that patriotism and that gung-ho dedication to a team effort. That describes my band to this day."

Looking back on those days after leaving Night Ranger, Blades remembers feeling like he had something to prove, and being thrilled to have the opportunity to branch out in different ways. "I was a positive, push-forward guy, it felt like 'This isn't over,'" he says. "I still had so much music inside of me. So many ideas. So much everything inside of me, so it was like 'Shit! Let's go full speed ahead!'"

"You know, that first album, in the little CD booklet, it has this huge collage of photographs," points out Cartellone. "That collage of photos really illustrates visually the journey of the building of this band and going to each other's houses. It really captures the way that this thing became just like a fun group of people that just really enjoyed hanging out together. You’ll see in there that there’s pictures of us fishing together and it became like a real brotherhood before it even became a band. ... I’ve been very happily a member of Lynyrd Skynyrd for 17 years now and I’m still referred to as 'that guy from Damn Yankees.' I couldn’t be happier about it."

So are the Damn Yankees finished for good? Probably, says Nugent, who has admitted in the past to being a big reason for the group's long hiatus. Still, there's a slight chance we could hear more from the band. "I don’t end my hope. I do hope so," Nugent says.

"I might just get out the cattle prod and visit Mr. Shaw and Blades and Cartellone and go, 'Uh, gentlemen, how about a song, at least? Let’s all get together and make at least a song. Let’s spend two days eating barbeque, shoot machine guns and let’s make a song!' That’s what I predict," Nugent chuckles. "That sounds exciting, doesn’t it?"

Forgotten First Albums: Rock's 61 Most Overshadowed Debuts

You Think You Know Damn Yankees?

More From Kool 107.9