Revisiting the ‘Forgotten Woodstock’ of 1989

As the ‘80s drew to a close, the world was a very different place from how it had been two decades earlier. The political impact of ‘60s counterculture had been absorbed into the constantly changing human rat race; recorded by analysts and remembered by those who took part, it seemed important but most certainly in the past.

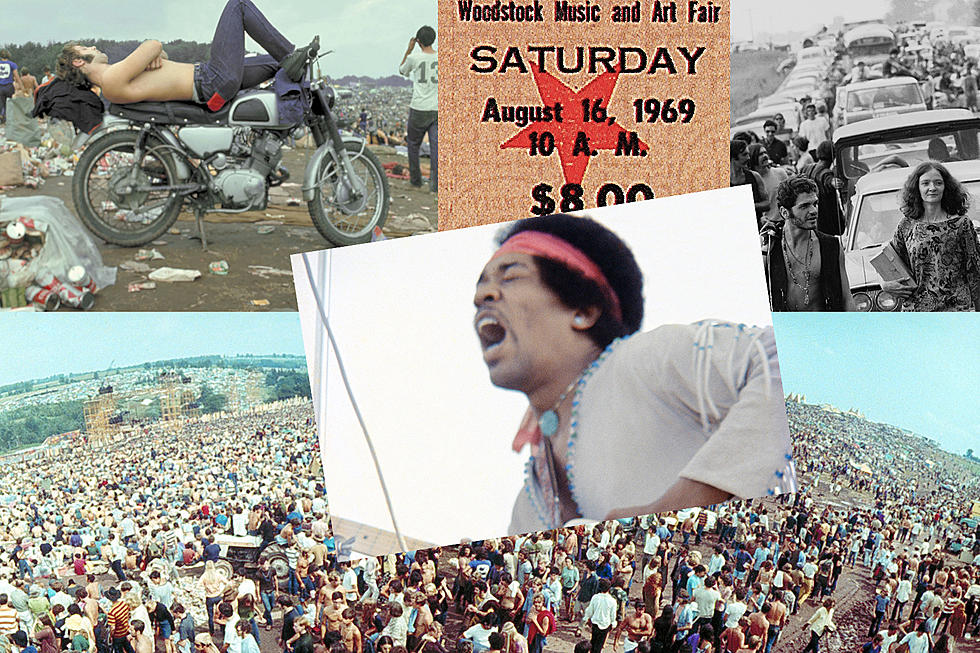

As the 20th anniversary anniversary of the iconic Woodstock festival approached, there was general agreement that it should be marked. But it seemed like something to be talked about, not acted upon, and as a result there was no official attempt to stage a large-scale celebration. After all, hadn’t Woodstock been a once-in-a-lifetime happening?

“Nobody I know who was in the audience is taking the occasion to celebrate in any significant way,'' cultural history author Joel Makower told The New York Times in a piece titled “Wallowing Again in Mud and Nostalgia.” “I get the sense that all the celebrating is being done for them, by media, by musicians and producers and, for better and for worse, by all the marketers of boxer shorts and air fresheners with the Woodstock logo on them.”

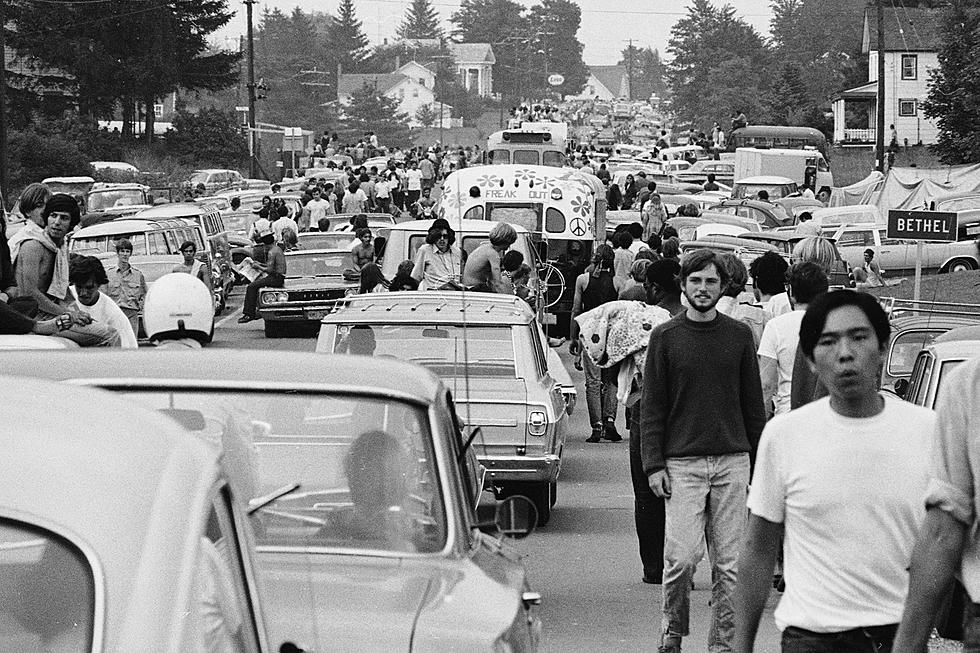

That appeared to be the feeling across the media. Papers published flashback pieces and magazines interviewed those who had been there, and the sense of past tense was prominent. On the morning of Tuesday, Aug. 15, 1989 – the anniversary date – TV network crews arrived at Bethel to film scenes of around 1,500 “nostalgia hunters” who’d made an anniversary pilgrimage to the place where it had happened, then went home … and in doing so missed the real story.

Watch a Woodstock '89 News Report

A few weeks earlier, folk musician Rich Pell had been given permission to stage a concert at the original site. Accounts suggest he had no expectations over how many might attend, though he’d done his best to provide staging, toilets and other basics. He and a group of people simply wanted to celebrate Woodstock and had no ambition of creating another happening, so having no advertising budget wasn’t an issue. What Pell and company couldn’t know is that many others felt the same way, but, with no official event to attend, they’d quietly made the decision to head to Bethel just to be there for the anniversary.

When the TV crews left, several hundred people were at the site. But as the music began at 5.07PM – the exact time Richie Havens started the show 20 years earlier – it became clear that many others were on their way. By Wednesday evening, it’s estimated more than 7,000 people were in attendance. By Friday, the figure was said to be 30,000.

“Most people seemed to have made a spontaneous decision to come to the festival site,” journalist Stu Fox wrote at the time. “Long Islanders Bob Saul and John Hirsch had come 20 years ago. According to Saul, ‘On Sunday we said, Let’s go to Woodstock. We hopped in the car and went.’ Freddy from Charlotte ‘just decided to come’ while watching the movie on television. John Withers, a 46-year-old New Jersey history teacher, drove three hours just to spend a few hours at the site. And Jimbo came all the way from Weiser, Idaho, ‘just because it’s Woodstock.’ … Joe and Gina Evagues of Murfreesboro, Tenn., spent three days in their car out by the main entrance because as Joe put it, ‘I always knew I’d come here. This is where I belong.’ … For Dominick Dell’Erba of Maryland, “The thing I came down for was the sense of community.” Leif, 37, a lab technician and Woodstock veteran, returned ‘to remind myself where I came from.’ Kit, 39, from Indiana, was there because ‘this is like coming back home.’”

Watch Scenes From Woodstock ’89

As word spread and more people appeared at Woodstock, local bands provided equipment to stage a larger-scale performance, while essential services were managed by volunteers. An attempt to charge a $5 parking fee to help defray costs was abandoned, and it was reported that very few commercial operations were seen at the event.

Highlights included a lunar eclipse on Wednesday, Aug. 16, during which there was a crowd-powered attempt to “call down the moon,’ led by Jack Hardy. Al Hendrix, father of Jimi Hendrix, told the crowd, “Everybody’s here in the spirit of Woodstock;” and original performers Melanie and Savoy Brown made a return. Hundreds of unannounced bands turned up and waited for an opportunity to take part. Original promoter Michael Lang made an appearance, as did Hugh “Wavy Gravy” Romney, who managed the freak-out tents in 1969. (He was in the area to attend the semi-official Remember Woodstock concert in nearly Swan Lake, but abandoned it for the Bethel event, as did almost everyone else involved.)

“They were there for nothing other than to be there,” Melanie told a California audience days after her appearance at Bethel. “It was so amazing. The people in the town built a makeshift stage and local bands were playing, and I went down there and I got to sing at Woodstock. So I did it twice in one lifetime!”

While the attendance will never be known, Fox reported that 50,000 signatures were added to the Woodstock monument guest book (though, according to The New York Times, one of those was “Janis Joplin”) and that many more people arrived after the 1989 festival was over. “A community was formed,” he said. “People of all ages and backgrounds came together to enjoy themselves and each other. … The reborn Woodstock Nation generated its own services, culture and customs. Everything was dependent upon the efforts of volunteers. … And the people were the friendliest group this writer has ever encountered.”

Watch Jack Hardy Call Down the Moon at Woodstock ’89

The “forgotten Woodstock” had such an impression on Pell and others that they took to organizing annual events, though none reached the dizzy heights of the 1989 edition, and they were later overtaken by official Woodstock festivals.

But none of that mattered to Pell, who recalled in 1994 that they were "trying to do a real righteous thing. What we’re all about is exercising our rights of freedom of speech and the pursuit of happiness. … I think it goes even beyond the music. I think it gets to people getting together in a spirit of giving and kindness and of compassion for one another. It was really something special that people have remembered all these years – the peace and love are the true Woodstock spirit.”

10 Artists You Didn't Know Played Woodstock

More From Kool 107.9