That Time Canned Heat and John Lee Hooker Made ‘Hooker ‘n Heat’

Plenty of rock bands in the '60s and '70s owed a huge debt to blues legends. Few made as sincere, or as overt, an effort to repay that debt as Canned Heat did with 1971's Hooker 'n Heat.

The band's seventh album, Hooker 'n Heat caught Canned Heat near their commercial peak. Although their fealty to classic blues would always make them an awkward fit for the Top 40 — and their constant lineup changes made maintaining a consistent sound more difficult than it should have been — they'd managed to parlay appearances at Woodstock and the 1967 Monterey Pop Festival into a string of radio hits that included "On the Road Again," "Going Up the Country" and "Let's Work Together." They were, in other words, perfectly poised to do a solid for one of the artists who laid the foundation for their work.

More than most of their contemporaries, the members of Canned Heat appreciated this responsibility. Co-founder Alan "Blind Owl" Wilson was a Massachusetts native and a music major at Boston University, but his career path diverged wholly from the tweed stereotype his biography might suggest; in fact, he was such an ardent student of classic blues recordings that when Son House was "rediscovered" in the early '60s, it was Wilson who taught him how to play his songs again. Along with Canned Heat co-founder Bob Hite, Wilson was also responsible for getting pianist Sunnyland Slim back into the studio after a long period spent toiling in obscurity.

Guitarist Henry Vestine, meanwhile, learned to play guitar alongside his childhood friend John Fahey, who later offered the key introductions that led to Canned Heat coming together — and drummer Adolfo de la Parra had served time backing a long list of artists that included Etta James and the Shirelles. For all these reasons and more, this was a band with a deep appreciation of their roots, so when the opportunity to record with John Lee Hooker came along, they made the absolute most of it.

Hooker had been recording since 1948, and he'd scored a watershed early hit with his early single "Boogie Chillen'," but none of his full-length albums had charted nationally, and due to a series of bad deals, he was deprived of songwriting credit on a number of his classic compositions. Though he wasn't exactly living in obscurity, he wasn't benefiting monetarily from the wave of blues-influenced rock that was currently in vogue, either — at least not until Hooker 'n Heat.

Not only did Hooker receive top billing on the release, he was given the first of the double-LP set's platters for a run of solo performances. For much of Hooker 'n Heat's first 10 tracks, the only sounds the listener hears are Hooker's voice, guitar and stomp; it isn't until the album's 13th track, "Whiskey and Wimmen," that a drum set makes its first appearance.

If they were eager to yield the spotlight to Hooker, Canned Heat still left themselves more than enough room to make an impression. Even though Hooker 'n Heat shifts somewhat slowly from Hooker's solo set to a full-band performance, there's no denying that this group of musicians worked well together, and several numbers — including the album-closing jam session "Boogie Chillen No. 2" — run upward of seven minutes thanks to the songs' jam-friendly arrangements.

The result wasn't Canned Heat's biggest hit, but it offered a long-overdue introduction to a living blues legend for many listeners — and after peaking at No. 78 on the Billboard chart, it gave Hooker his best-selling album to that point, helping usher in an era of greater success and leading to a higher profile on the touring circuit, where he continued to spend much of his time.

For Canned Heat, Hooker 'n Heat ultimately proved a slightly bittersweet experience. Wilson had battled depression for years, and was spending his nights at a psychiatric facility while the album was being tracked; although band members hoped the experience of recording alongside Hooker might help revitalize their friend, he died before the record was released, succumbing to what was determined to be accidental acute barbiturate intoxication in September 1970.

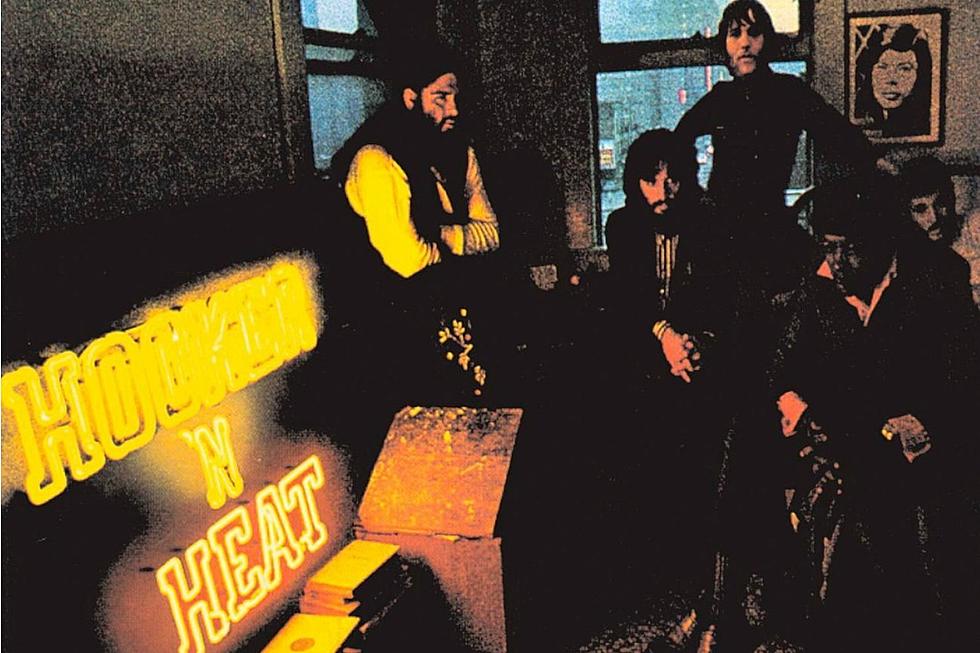

Yet even in the absence of Wilson (who's glimpsed in a photo on the wall on the Hooker 'n Heat album cover), the band continued to soldier on, and remains a going concern even after countless trend shifts and lineup changes. They'd also reunite with Hooker on a number of occasions, including a 1978 tour (commemorated on 1981's Hooker 'n Heat Live at the Fox Venice Theatre) and an appearance on Hooker's next comeback effort, 1989's all-star album The Healer. Hooker himself died in 2001, at the age of 83 and after recording more than 100 albums; like the rest of his many classics, Hooker 'n Heat still sounds so urgent and vital that it might as well have been recorded yesterday.

See the Top 100 Rock Albums of the ‘70s

More From Kool 107.9